$3.46M to Combine Machine Learning on Big Data with Physical Simulations

The focal point of the project will be a new computing resource, called ConFlux, which is designed to enable supercomputer simulations to interface with large datasets while running.

Enlarge

Enlarge

A new way of computing could lead to immediate advances in aerodynamics, climate science, cosmology, materials science and cardiovascular research. The National Science Foundation is providing $2.42 million to develop a unique facility for refining complex, physics-based computer models with big data techniques at the University of Michigan, with the university providing an additional $1.04 million.

The focal point of the project will be a new computing resource, called ConFlux, which is designed to enable supercomputer simulations to interface with large datasets while running. This capability will close a gap in the U.S. research computing infrastructure and place U-M at the forefront of the emerging field of data-driven physics. The new Center for Data-Driven Computational Physics will build and manage ConFlux. Prof. Barzan Mozafari is co-PI of the center and will oversee implementation of ConFlux.

“Scientists have long been using HPC clusters for their heavy computations, while the Hadoop ecosystem has largely catered to the enterprise world. This ConFlux instrument is a unique opportunity to marry these disconnected worlds. Here, at the University of Michigan, we have identified a crucial class of open problems in computational physics that now can be tackled with this type of hybrid cluster.” said Prof. Mozafari.

The project will add supercomputing nodes designed specifically to enable data-intensive operations. The nodes will be equipped with next-generation central and graphics processing units, large memories and ultra-fast interconnects.

Advanced Research Computing – Technology Services at University of Michigan provided critical support in defining the technical requirements of ConFlux. The project exemplifies the objectives of President Obama’s new National Strategic Computing Initiative, which has called for the use of vast data sets in addition to increasing brute force computing power.

The common challenge among the five main studies in the grant is a matter of scale. The processes of interest can be traced back to the behaviors of atoms and molecules, billions of times smaller than the human-scale or larger questions that researchers want to answer.

Even the most powerful computer in the world cannot handle these calculations without resorting to approximations, said Karthik Duraisamy, an assistant professor of aerospace engineering and director of the new center. “Such a disparity of scales exists in many problems of interest to scientists and engineers,” he said.

But approximate models often aren’t accurate enough to answer many important questions in science, engineering and medicine. “We need to leverage the availability of past and present data to refine and improve existing models,” Duraisamy explained.

This data could come from accurate simulations with a limited scope, small enough to be practical on existing supercomputers, as well as from experiments and measurements. The new computing nodes will be optimized for operations such as feeding data from the hard drive into algorithms that use the data to make predictions, a technique known as machine learning.

“Big data is typically associated with web analytics, social networks and online advertising. ConFlux will be a unique facility specifically designed for physical modeling using massive volumes of data,” said Prof. Mozafari.

The faculty members spearheading this project come from departments across the University, but all are members of the Michigan Institute for Computational Discovery and Engineering (MICDE), which was launched in 2013.

“MICDE is the home at U-M of the so-called third pillar of scientific discovery, computational science, which has taken its place alongside theory and experiment” said Krishna Garikipati, MICDE’s associate director for research.

The following projects will be the first to utilize the new computing capabilities:

- Cardiovascular disease. Noninvasive imaging such as MRI and CT scans could enable doctors to deduce the stiffness of a patient’s arteries, a strong predictor of diseases such as hypertension. By combining the scan results with a physical model of blood flow, doctors could have an estimate for arterial stiffness within an hour of the scan. The study is led by Alberto Figueroa, the Edward B. Diethrich M.D. Research Professor of Biomedical Engineering and Vascular Surgery.

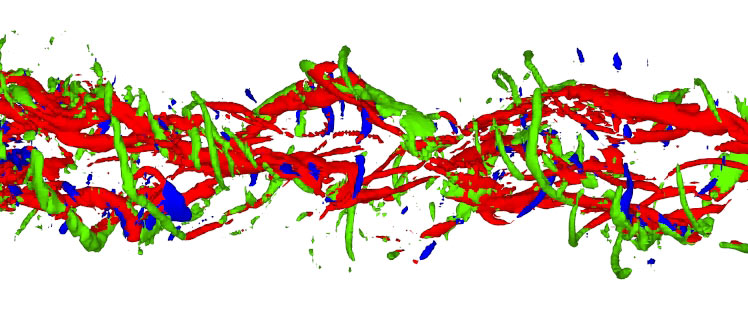

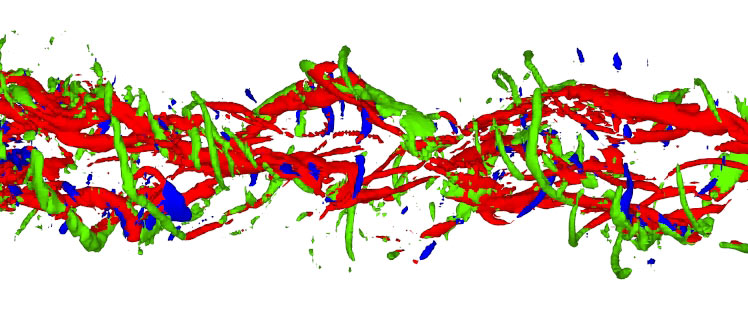

- Turbulence. When a flow of air or water breaks up into swirls and eddies, the pure physics equations become too complex to solve. But more accurate turbulence simulation would speed up the development of more efficient airplane designs. It will also improve weather forecasting, climate science and other fields that involve the flow of liquids or gases. Duraisamy leads this project.

- Clouds, rainfall and climate. Clouds play a central role in whether the atmosphere retains or releases heat. Wind, temperature, land use and particulates such as smoke, pollen and air pollution all affect cloud formation and precipitation. Derek Posselt, an associate professor of atmospheric, oceanic and space sciences, and his team plan to use computer models to determine how clouds and precipitation respond to changes in the climate in particular regions and seasons.

- Dark matter and dark energy. Dark matter and dark energy are estimated to make up about 96 percent of the universe. Galaxies should trace the invisible structure of dark matter that stretches across the universe, but the formation of galaxies plays by additional rules – it’s not as simple as connecting the dots. Simulations of galaxy formation, informed by data from large galaxy-mapping studies, should better represent the roles of dark matter and dark energy in the history of the universe. August Evrard and Christopher Miller, professors of physics and astronomy, lead this study.

- Material property prediction. Material scientists would like to be able to predict a material’s properties based on its chemical composition and structure, but supercomputers aren’t powerful enough to scale atom-level interactions up to bulk qualities such as strength, brittleness or chemical stability. An effort led by Garikipati and Vikram Gavini, a professor and an associate professor of mechanical engineering, respectively, will combine existing theories with the help of data on material structure and properties.

“It will enable a fundamentally new description of material behavior—guided by theory, but respectful of the cold facts of the data. Wholly new materials that transcend metals, polymers or ceramics can then be designed with applications ranging from tissue replacement to space travel,” said Garikipati, who is also a professor of mathematics.

MENU

MENU